- Home

- Lisa Chaney

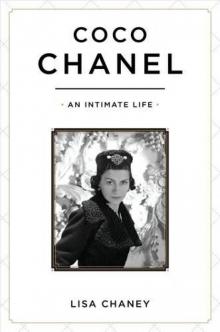

Coco Chanel: An Intimate Life

Coco Chanel: An Intimate Life Read online

Coco Chanel: An Intimate Life

Lisa Chaney

The controversial story of Chanel, the twentieth century's foremost fashion icon.

Revolutionizing women's dress, Gabrielle "Coco'' Chanel was the twentieth century's most influential designer. Her extraordinary and unconventional journey-from abject poverty to a new kind of glamour- helped forge the idea of modern woman.

Unearthing an astonishing life, this remarkable biography shows how, more than any previous designer, Chanel became synonymous with a rebellious and progressive style. Her numerous liaisons, whose poignant and tragic details have eluded all previous biographers, were the very stuff of legend. Witty and mesmerizing, she became muse, patron, or mistress to the century's most celebrated artists, including Picasso, Dalí, and Stravinsky.

Drawing on newly discovered love letters and other records, Chaney's controversial book reveals the truth about Chanel's drug habit and lesbian affairs. And the question about Chanel's German lover during World War II (was he a spy for the Nazis?) is definitively answered.

While uniquely highlighting the designer's far-reaching influence on the modern arts, Chaney's fascinating biography paints a deeper and darker picture of Coco Chanel than any so far. Movingly, it explores the origins, the creative power, and the secret suffering of this exceptional and often misread woman.

Lisa Chaney

Coco Chanel: An Intimate Life

For Anna

(And in memory of our mother, Elizabeth [1923–2009])

“Capel said, ‘Remember that you’re a woman.’

All too often I forgot that.”1

INTRODUCTION

Gabrielle (Coco) Chanel was a woman of singular character, intelligence and imagination. These attributes enabled her to survive a childhood of deprivation and neglect and reinvent herself to become one of the most influential women of her century. Unlike any previous female couturier, her own life quickly became synonymous with the revolutionary style that made her name. But dress was only the most visible aspect of more profound changes Gabrielle Chanel would help to bring about. During the course of an extraordinary and unconventional journey — from abject poverty to the invention of a new kind of glamour — she helped to forge the idea of modern woman.

Leaving behind her youth of incarceration in religious institutions, Gabrielle became a shop assistant in a town thronging with well-to-do young military men from the regiments stationed on its perimeter. She then threw away any chance of respectability by becoming mistress to one of them, and over the years her numerous subsequent liaisons were much talked about. Her relationship with Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich was a remarkable reflection of changing times, while that with the fabulously wealthy Duke of Westminster was the stuff of legend. Her love affair with one of Europe’s most eligible men, the enigmatic playboy Arthur Capel, enabled her to flourish, but would end in tragedy.

Aside from her dark beauty, Gabrielle was described as “witty, strange, and mesmerizing.” She would become the muse, patron, collaborator or mistress of a number of remarkable men, including some of the most celebrated artists of modern times. These included: Picasso, Cocteau, Stravinsky, Visconti, Dalí and Diaghilev. In addition, Gabrielle rose to the highest echelons of society; created an empire; acquired the conviction that “money adds to the decorative pleasures of life, but it is not life”; became a quintessential twentieth-century celebrity and was transformed into a myth in her own lifetime.

To those already interested in her, the general outline of her life is well-known. Gabrielle’s story is one of drama and pathos, and I had become intrigued, though I doubted that there was much left to discover. Her first biographer, Edmonde Charles-Roux, appeared to have found all that the passage of time and Gabrielle’s concealment of her past would permit. Subsequent biographers had accepted this state of affairs, and thus various periods in her life remained unknown. My interest had been caught, though — among other things, by the variety and caliber of artists whom she had known, artists instrumental in the creation of modernism in early twentieth-century bohemian Paris. Simply retelling the rags-to-riches narrative and listing the sartorial changes she is credited with inventing don’t do justice to a woman who played a part in the formation of the modern world, not only its clothes but its culture.

As I became more familiar with her story, the gaps grew more tantalizing. While that first biographical interpretation had stamped itself upon the general perception of the woman who became Coco Chanel, intuition told me things were subtly different. She left behind few letters and no diaries. Believing, nevertheless, that I might be able to turn up some new details, I embarked on early reconnaissance. Little did I know then the trails I was to follow and the raft of discoveries I would be fortunate enough to make over the next four years. As these new elements of her story gradually fell into place, more light was in turn thrown on Gabrielle’s character.

Her dreadful childhood was obviously critical, but while her own version shifted like the sands, I found treasures once I had learned how to filter her storytelling. Gabrielle often tells us as much about herself in what she left out or altered as in what she chooses to reveal. Approaching her from a peripheral viewpoint was also fruitful. Had so-and-so known her? If so, what had been written up in his or her diaries or letters? One line here, another there in a letter or an interview became crucial to the expanding story.

I traveled to Ireland to meet Michel Déon, who had spent a great deal of time with Gabrielle sixty years before. As a successful young novelist he had been commissioned to write her biography. I returned with no new “facts” but something more important. Michel Déon had regaled me with anecdotes, interspersed with the sharpest of observations. At the same time his compassion for her was instrumental in the development of my ability to comprehend her lifelong emotional plight. Her vulnerability was largely concealed, but it contributed to her isolation.

The reminiscences of those who had known her were invaluable, but other sources were also critical. An introduction to the American Russianist William Lee, for example, brought about his translations of a number of Duke Dmitri Pavlovich’s diary entries, sent to me via installments over several weeks. These have revised our understanding of Dmitri and Gabrielle’s affair. They reveal quite a different relationship from the one traditionally described, which has Gabrielle the man-eater being mooned over by the young aristocrat.

My confirmation of Gabrielle’s rumored bisexuality and drug use is important. Other discoveries were perhaps even more so, because they opened up deeper, sometimes disturbing questions about her.

After months of searching, one day I sat with the son-in-law and grandson of Arthur Capel, unquestionably the great love of Gabrielle’s life. His family had no more than snippets of information about their elusive forebear. This included the complex triangular relationship involving him, Gabrielle and the woman he would marry instead, Diana Wyndham. But what I heard that day set me on the trail of this extraordinary man — who Gabrielle said had made her — and the discovery of the poignant details of their affair.

During part of the Second World War, Gabrielle lived in occupied Paris at the Ritz with Hans Günther von Dincklage, a German. The other “guests” were German officers. It was already established that von Dincklage had done some prewar spying for his government. On meeting Gabrielle, according to the standard story, this had ceased and he had become “antiwar.” Gabrielle and von Dincklage’s affair, and his wartime activities, have been only partially known. However, a cache of documents about von Dincklage in the Swiss Federal Archives, some in the French Deuxième Bureau and yet more information in other unlikely places have made it possible to give a fuller account of this reprehe

nsible man than ever before. A master of seduction and deception, he was without question a spy. Yet while Gabrielle was undoubtedly a survivor, I don’t believe she ever knew this. Nevertheless, after the war she thought fit to remove herself to neutral Switzerland so as to avoid any possible proceedings against her.

Having closed her couture house during the war, in 1954 she returned to it. At first a failure, in time she once again became a world-class couturier. Her myth, which she nurtured, grew until it was sometimes impossible to distinguish it from the real woman. As one of the pioneers of modern womanhood Coco Chanel personified one of its greatest dilemmas: fame and fortune versus emotional fulfillment. Her myth was sometimes a substitute; by the end of her life she had little else. Her carapace of inviolability, her wall of self-protection raised up over the years, meant that few were able to reach her. In her last years, increasingly autocratic, she remained formidable. Her loneliness was sometimes tragic.

After her death, Chanel continued with increasing success, constantly reinventing her themes. As a result, the mythic Coco Chanel is now a global icon far outstripping what she was in her own lifetime. I make no claim to have uncovered everything or to have solved all of the mysteries Gabrielle Chanel left behind. But in illuminating some of them, and in presenting her without sentimentality yet with all of her pathos and seductive complexity, I hope I have helped humanize this deeply complex character, one of the most remarkable women of the last century.

Gabrielle Chanel moved to Switzerland after the Second World War. It was there that she asked a friend, the writer and diplomat Paul Morand, to take down her memoirs. She left behind no diaries and only a handful of letters, but after her death, Morand was persuaded to publish the notes from those evenings in Switzerland. No other primary source gives as much insight into Gabrielle’s extraordinary life as Morand’s book, her memoir,

The Allure of Chanel.

Gabrielle’s own words ring out in the description that follows of an event that would alter the course of her life.

PROLOGUE. You’re Proud, You’ll Suffer

One night, just over a century ago, a couple made their way past the Tuileries, the oldest of Paris’s gardens. They were to dine in Saint-Germain the neighborhood where the loftiest nobility still kept mansions in town.

The young woman was straight and slender. Her heavy black hair was caught up at the nape of a long neck, and an unusually simple hat set off her angular beauty. She looked younger than her twenty-six years. Her English lover’s gaze was skeptical, amused, revealing the confidence of privilege. His manner was, intentionally, less polished and urbane than that of his French peers.

As they went on, Gabrielle (who was known to some as Coco) talked. Enjoying her newfound independence, acquired with the progress of her little business, she remarked on how easy it seemed to be to make money. She was unprepared for her lover’s response.

He told her she was wrong. Not only was she not making any money, she was actually in debt to the bank.

She refused to believe him. If she wasn’t making any money, why did the bank keep giving it to her?

Her lover, Arthur Capel, laughed. Hadn’t she realized? The bank gave her money only because he’d put some there as a guarantee. But she challenged him again.

“Do you mean I haven’t earned the money I spend? That money’s mine.”

“No, it isn’t, it belongs to the bank!”

Gabrielle was shocked into silence. Keeping stride with her quickened pace, Arthur told her that, only yesterday, the bank had telephoned to say she was withdrawing too much.

While her talk of business had provoked Arthur to reveal the truth of her situation, he didn’t much care and he told her it really wasn’t important. This attempt to mollify her only renewed her defiance.

“The bank rang you? Why not me? So I’m dependent upon you?”1

In despair, she now insisted they go back across the river, but this brought her no respite. Looking around their well-appointed apartment, she saw the objects she had purchased with what she had thought to be her profits and was faced with the illusion of her independence. Everything had really been bought by Arthur. Her despair turning to hatred, she hurled her bag at him, ran down the stairs and out into the street. Heedless of the rain, she fled, intent on seeking refuge several streets away in her shop on the rue Cambon.

“Coco, you’re crazy!” Arthur called out.

By the time he reached her, though they were both soaked, his instruction to her to be reasonable was useless and she sobbed, inconsolable.

In his arms, she was at last calmed. “He was the only man I have loved,” she would say in later years. “He was the great stroke of luck in my life… He had a very strong and unusual character… For me he was my father, my brother, my entire family.”2 Yet only after much persuasion would she return to their apartment. In the early hours, when Arthur believed he had soothed the wound to her pride, at last, they both slept.

This experience transformed her purpose. A few hours later, arriving early at rue Cambon, she made a pronouncement to her head seamstress, Angèle: “From now on, I am not here to have fun; I am here to make a fortune. From now on, no one will spend one centime without asking my permission.”3

When Arthur shocked Gabrielle out of her fantasy and laughed at her self-delusion, even he, who understood her well, could not have predicted the ferocity of her response. He had done her a harsh favor, had compelled her to face reality. This was the catalyst that would release her most intense creative energies.

Coco Chanel would never forget Arthur’s part in initiating her transformation. And if he had at first underestimated the degree to which her pride was the force that drove her, he was nonetheless the one who had said to her, “You’re proud, you’ll suffer.”4

In these words, he had singled out Gabrielle’s most significant driving force and foreseen that it would be the source of her vulnerability. Yet while her pride was indeed to make her suffer, she believed it was the key to her success. “Pride is present in whatever I do,” she would later say. “It is the secret of my strength… It is both my flaw and my virtue.”5

Some time after the night that drove her to her new purpose, her business began to prosper, and she would emerge from her understudy role as a kept young woman with a hat shop. As her rebellious and progressive style gradually became synonymous with her controversial life, Coco Chanel would embody an influential and glamorous new form of female independence. Later, she would say, “But I liked work. I have sacrificed everything to it, even love. Work has consumed my life.”6

In the meantime, as her profits became substantial, she proudly told Arthur she no longer needed a guarantor and that he could withdraw all his securities. His reply was melancholy: “I thought I’d given you a plaything, I gave you freedom.”7

1. Forebears

While state roads have carved up our landscapes with a rigorous efficiency, leaving few places distant or mysterious, the region of Gabrielle Chanel’s paternal ancestors, the Cévennes, retains a strong sense of its earlier remoteness. One of France’s oldest inhabited regions, it is a complex network of peaks, valleys and ravines that form the southeastern part of the Massif Central. Cut off from the Alps to the east by the cleft of the river Rhône, its vast limestone plateaus, dissected by deep river gorges, were traditionally the preserve of shepherds and their sheep. By the eighteenth century, the valleys of the Cévennes were dependent upon silk farming and weaving and the cultivation of the mulberry. Below the highest peaks, fit only for pasture, millions of chestnut trees, long a source of income for locals, still dominate the landscape.

In 1792, only three years after the revolution, Joseph Chanel, Gabrielle’s great-grandfather, was born in Ponteils, a hamlet of stone houses surrounded by chestnut groves. As a journeyman carpenter, he used his fiancée’s modest dowry to set himself up as Ponteils’ tavern keeper in part of a large farmhouse standing on a little knoll above the village. In time, the farmhouse became kno

wn as The Chanel, a name it retains to this day. The tough and forthright Cévenol mentality, which enabled the local early Protestants, the Huguenots, to withstand terrible persecution appears to have passed down the Chanel line. In years to come, Gabrielle’s friend Jean Cocteau would say: “If I didn’t know she was brought up a Catholic, I would imagine she was a Protestant. She protests inveterately, against everything.”1

Today, the only memorial to any of the Chanels is Joseph’s tavern. The Chanels of Ponteils were unexceptional; theirs were the lives of countless country people. Between 1875 and 1900, the region was hit by a series of exceptional natural disasters. Phylloxera ravaged the vines in the lowlands; silkworm farmers reeled from the effects of a silkworm disease epidemic; and the vast chestnut forests of the uplands were eaten up by la maladie de l’encre, a disease specific to the species. With the core of the rural economy devastated, the villagers of Ponteils could struggle on for only so long. Thousands in the region forsook their birthplace in search of work, and between 1850 and 1914, the population of the Cévennes dropped by more than half.

Joseph Chanel’s second son, Henri-Adrien — Gabrielle’s grandfather — and his two younger brothers were among those whom la maladie de l’encre forced to leave Ponteils. As mountain dwellers, their skills weren’t much use down in the valleys, but eventually Henri-Adrien found work with a silk-farming family, the Fourniers, in Saint-Jean-de-Valériscle. Youth, ignorance and a taste for adventure permitted him the luxury of confidence. This same confidence soon led him to impregnate his employer’s sixteen-year-old daughter.

Virginie-Angélina’s parents’ fury was intense and they insisted that Henri-Adrien should marry their compromised offspring. The prospect of Virginie-Angélina’s dowry may have been the deciding factor in the young man’s compliance. Soon after the ceremony, the newlyweds left the silk farm for Nîmes.

Coco Chanel: An Intimate Life

Coco Chanel: An Intimate Life Coco Chanel

Coco Chanel